How Great Ideas Sometimes Come From Following the Natural Flow of Things

Image: James Homans on Unpslash

GUEST POST from John Bessant

Sometimes it’s the simplest ideas which change the world. Barbed wire is nothing more than a cleverly twisted piece of metal, yet its role in taming the Wild West was much more significant than any cowboys or cavalry. It enabled settlers to graze their herds and property rights to be marked out and defended.

Joe Woodland’s idle scratches in the sand on a Miami beach were the prototype for what became known as the Universal Product Code — and paved the way for bar codes identifying everything from supermarket items to surgical implants.

And a simple metal box transformed the pattern and economics of world trade. Brainchild of Malcolm McLean containerisation changed the way goods were transported internationally, drastically cutting costs and saving time. In 1965 a ship could expect to remain in port being loaded or unloaded for up to a week, with transfer rates for cargo around 1.7 tonnes/hour. By 1970 this had speeded up to 30 tonnes/hour and big shops could enter and leave ports on the same day. Journey times from door to door were cut by over half and the ability to seal containers massively cut losses due to theft and consequently reduced insurance costs.

McLean was a tough entrepreneur who’d already built a business out of trucking. He’d learned the rules of the innovation game the hard way and knew that having a great idea was only the start of a long journey. Realising the value at scale would take a lot of ingenious problem-solving and systems thinking to put the puzzle together. He needed complementary assets — the ‘who else?’ and ‘what else?’ — to realise his vision. And he understood the challenge of diffusion — getting others to buy into your idea and enabling adoption through a mixture of demonstration, persuasion and pressure.

But he wasn’t the first to come up with the idea; that distinction probably goes to another systems thinker who played the innovation game well throughout his unfortunately short life. And, like McClean, he can take a big share of the credit for transforming the pattern of world trade, this time in the 18th century.

Image: David Dibert on Pexels

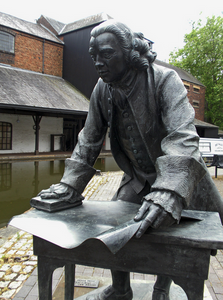

James Brindley was born in 1716 and spent his early years learning the hard way about how things work — and how to make them work better. He didn’t have much of a formal education, could barely read or write and worked as an agricultural labourer until he was 17. He used his savings to buy his way into an apprenticeship to a millwright, one Abraham Bennett. Bennett was an engineer who preferred to leave much of the work in his business to others while he relaxed (and drank away) the fruits of their labour. Which offered James an opportunity not only to learn fast but to try out ideas. He’d grown up around mills, (both wind and water driven) and was fascinated by their operations.

He got a chance to put some of his innovative ideas into practice when he was given the task, in 1735 of carrying out emergency repairs to a small silk mill. His work so impressed the mill superintendent that he recommended Brindley to others; it wasn’t long before he’d acquired enough experience and skill from different projects to set up on his own as a millwright. He earned the nickname of ‘the Schemer’ because of his approach which was often unconventional but certainly delivered results.

Photo by Ali Arapoğlu from Pexels

Which is how he came to be associated with the Wedgwood brothers who were busy establishing their ceramics business in nearby Stoke on Trent. They sought him out to help with problems they were having in grinding flint, one of the key ingredients in their pottery. Brindley built a series of mills for them, finding ways to improve efficiency and cut costs, and consolidating his reputation They in turn recommended him to John Heathcote, owner of the large Clifton collieries near Manchester who was struggling with a big problem of flooding in his mines.

Brindley’s solution seemed crazy at first — he proposed drawing in more water! But in fact his ingenious idea was to draw water from the nearby river Irwell, pass it through an underground tunnel nearly a kilometre in length and use it to drive a huge mill wheel which drove a pump. It was strong enough to pump out the mine and efficient since it returned the water to the river. It worked — and established his reputation not just as a skilled engineer but as an imaginative problem-solver and innovator.

No-one could call him a lazy man — he worked incessantly on a wide range of projects. But he also spent a lot of time in bed — sometimes days at a time. This was his thinking space, a way of incubating novel and sometimes crazy ideas.

And water was at the centre of his thinking; he seemed to have an intuitive grasp of how it flowed and how those principles could be applied in a wide variety of situations. As he famously replied to an early enquiry about how he had come up with a solution to a complex hydraulic problem he said ‘…it came natural-like…’

And of course one thing about water is that it requires you to think in systems terms, how things are linked together. Brindley had a gift for seeing the interconnected challenges in realising big schemes like the mine pumping system — and for focusing on solving those to enable the whole system to deliver value.

This approach stood him in good stead as he moved into the field for which we best know him — canals. Canals played a critical role in the early Industrial Revolution; they meant that raw materials could get in to factories and their finished products could find their way to ports and be exported around the world. Britain, as ‘the workshop of the world’ depended on the canals as the veins and arteries that enabled the giant to come to life.

And canals represented just the kind of systems challenge which Brindley was so good at. When the Duke of Bridgwater approached him in 1759 to help create a canal to connect his mines in Worsley to the city of Manchester he began a journey which would eventually see him changing the face of Britain, constructing 365 miles of canals criss-crossing the country and revolutionising productivity.

When the Bridgwater Canal was finished in 1761 it helped cut the price of coal in Manchester by 50% and it fell further over the coming years. He followed this with other major projects; he worked with the Wedgwoods to create the Trent and Mersey canal which linked the Potteries to the big industrial cities and ports, providing a way of climbing (through a total of 35 locks) the country and delivering their fragile wares to a global export market. Whether it was shipping coal, flint or other raw materials into cities or transporting their finished wares out to the great ports like Liverpool, Brindley’s canals connected the country.

Photo by Inge Wallumrød from Pexels

It wasn’t easy; quite apart from the eye-watering costs of construction building the canal posed many challenges. Brindley innovated his way around them, coming up with radical ideas for:

- using natural contours, working with the grain of the land rather than in straight lines. His canals might have been longer as a result but they were much cheaper to dig since this approach reduced the need for tunnels or expensive cuttings

- cutting narrower canals, which reduced the water consumption and hence the running costs. Of course to make these work required the design of narrow longer boats — something else which Brindley pioneered and which became the dominant design for the waterways

- pumping and circulatory systems to ensure efficient water flow into and tough the canal systems — and improving the design and productivity of the equipment involved

- raising and lowering boats as they traversed the country through a series of watertight locks, some of which survive to this day

- using puddling clay — a watertight ceramic material which he devised (using knowledge picked up from working with the Wedgwoods in their pottery factories) and which offered a watertight base with which to line the canals and solve the problem of water seepage

- imagining and realising things like the Barton viaduct, a bridge carrying the Bridgwater canal over river Irwell 12m below

Image: Watercolour of Barton aqueduct by G.F. Yates 1793, public domain

He also developed another innovation as part of his problem-solving for the coal industry. His narrow boats were nicknamed ‘Starvationers’ on account of the wooden braces across the hull which gave them strength. They looked like an emaciated torso but this design meant they were strong enough to haul tons of coal or iron ore. But there was a bottleneck in terms of loading and unloading and so Brindley designed a system of wooden containers for coal which could be filled and transhipped easily. His first boat with 10 containers began work in 1766, predating Malcolm McLean by close to 200 years.

(The concept was elaborated and really brought to the mainstream by James Outram who linked the idea into a system in which horses pulled containers from mines along rails to the canal where they were quickly transhipped. As the railways emerged to replace horse drawn traffic so this ‘intermodal system’ took off)

Water was what made him and indirectly it was the death of him. In 1771 he’d begun work on another visionary scheme, surveying the route of what was to become the Trent and Mersey canal. But he was caught in a heavy thunderstorm and drenched through. He wasn’t able to dry out properly at the inn where he was lodging and by the time he returned home he was severely ill; he died of pneumonia a few days later.

He left a legacy of innovation, both in the 365 miles of canals which he built and in the locks, pumping stations, tunnels and other engineering solutions to the problem of creating a viable water-based transport system.,

And he also offers a good reminder of some key innovation themes involved in bringing large scale ideas to fruition and having an impact at scale. He might have been nicknamed ‘the Schemer’, improvising his way to solving engineering problems, but he also understood things like:

- the importance of systems thinking and the need for complementary assets — identifying and putting in place the many interlocking pieces of the puzzle

- the value of prototypes and working models to help persuade and accelerate adoption. Legend has it that when he was presenting his ideas to a sceptical group of Members of Parliament whose approval he needed for the Bridgwater canal route he used a cheese out of which he carved a model of the aqueduct he proposed to build!

- the power of open innovation, learning from the many different sectors and projects he worked with and integrating knowledge from these different worlds — for example, using his knowledge of ceramics to develop the puddling clay liners for his canals

- the importance of business models in laying out the architecture through which ideas can create value. He not only understood the literal flow of water, he was also skilled at managing cash flow, acquiring a reputation for being ‘careful with money’ which undoubtedly helped realise some of the huge schemes with which he was involved.

![]() Sign up here to get Human-Centered Change & Innovation Weekly delivered to your inbox every week.

Sign up here to get Human-Centered Change & Innovation Weekly delivered to your inbox every week.

One of the best ways to challenge people’s thinking and get a group moving in a direction towards innovation is to get the group to define the box.

One of the best ways to challenge people’s thinking and get a group moving in a direction towards innovation is to get the group to define the box.

The new Starbucks train café is one of the smallest the company has ever designed, and they have managed to include space for 50 people, baristas, a pastry case, standing bar, and a lounge area, all tastefully assembled into a two level train car.

The new Starbucks train café is one of the smallest the company has ever designed, and they have managed to include space for 50 people, baristas, a pastry case, standing bar, and a lounge area, all tastefully assembled into a two level train car. It’s incredibly important for companies like Starbucks that sell daily indulgences to be in the places where people are looking to enjoy that little treat, and with the level of quality increasing (at least in the coffee experience) at competitors like Dunkin Donuts, McCafe, Caribou Coffee, and others, Starbucks has to do everything they can to reinforce their premium image and customer loyalty.

It’s incredibly important for companies like Starbucks that sell daily indulgences to be in the places where people are looking to enjoy that little treat, and with the level of quality increasing (at least in the coffee experience) at competitors like Dunkin Donuts, McCafe, Caribou Coffee, and others, Starbucks has to do everything they can to reinforce their premium image and customer loyalty.

In writing my article yesterday –

In writing my article yesterday –

I came across the C-1 from Lit Motors in an article by Donna Sturgess over on

I came across the C-1 from Lit Motors in an article by Donna Sturgess over on