Sometimes Letting Go is the Hardest Part of Innovation

GUEST POST from John Bessant

(You can find a podcast version of this story here)

The Welsh valleys are amongst the most beautiful in the world. Lush green hills steeply falling into gorges with silver water glistening below. It’s a place of almost perfect peace, the only movement the gentle trudge of sheep grazing safely, shuffling across the jagged landscape the way they’ve done for thousands of years. And amongst the most scenic and peaceful of these valleys are those situated between Dolgellau in the north, and Machynlleth in the south.

Except when there’s traffic in the ‘Mach loop’ — which is what the region is known as in military circles. It’s the place where young men and women from a variety of international air forces hone their skills at high-speed low-level flying, often as low as 75 meters from the ground. At any moment your peaceful walk may be rudely interrupted by the roar of afterburners, your view across the green hillsides suddenly broken by the nose of an F16 or Typhoon poking its way up from one of the gorges below.

Your reaction may be mixed; annoyance at the interruption or admiration for the flying skills of those pilots giving you a personal air display. But it’s certainly impossible to ignore. And it does raise an interesting question — despite the impressive skills being demonstrated, do we actually need pilots flying the planes? Is there an alternative technology which allows low level high precision flying but which can be carried out by an operator sitting far away in a remote location? After all we’ve become pretty good at controlling devices at a distance, can even land them on distant planets or steer a course through the furthest reaches of our universe.

UAVs — unmanned aerial vehicles — are undoubtedly changing the face of aviation. But are they also a disruptive innovation, particularly in the military world where the heroic tradition of those magnificent men (and women) in their flying machines is still so strong?

A brief history of drones

The idea of using unmanned flying vehicles isn’t new; back in 1839 Austrian soldiers attacked the city of Venice with unmanned balloons filled with explosives. During the early years following the Wright brothers successful flight researchers began looking at the possibilities of unmanned aircraft. The first prototype took off in 1916 in the form of the Ruston Proctor Aerial Target; as its name suggests it was a pilotless machine designed to help train British aircrew in dogfighting. Importantly it drew on early versions of radio control and was one the many brainchildren of Nikolai Tesla but its early performance was unremarkable and the British military chose to scrap the project, believing that unmanned aerial vehicles had limited military potential.

A year later, an American alternative was created: the Hewitt-Sperry Automatic Airplane and successful trials led to the development of a production version, the Kettering Bug in 1918. Although its performance was impressive it arrived too late to be used in the war and further development was shelved.

By the time of the Second World War the enabling technologies around control and navigation had improved enormously; whilst still crude the German V1 and V2 rockets and flying bombs provided a powerful demonstration of what could be achieved at scale. Emphasis was placed on remote delivery of explosives — using UAVs as flying bombs or aerial torpedoes — but the possibilities of using them in other applications such as reconnaissance were beginning to be explored.

The Vietnam war saw this aspect come to the fore; the difficulties of operating in remote jungle and mountain zones made reconnaissance flying hazardous and the risks to aircrew who were shot down led to extensive use of UAVs. The Ryan Firebee drone flew over 5000 surveillance missions, controlled by a ground operator using a remote camera. Its versatility meant that it could be used for surveillance, delivery of supplies and as a weapon; UAVs began to be viewed as an alternative to manned aircraft. But despite their success and promise it was not until the 1990s that they began to occupy an increasingly significant role.

The technology found more support in Israel and during the 1973 Yom Kippur war UAVs were used in a variety of ways, as part of an integrated approach alongside piloted aircraft. A great deal of learning in this context meant that for a while Israel became the key source of UAV technology with the US acquiring and deploying this knowledge to improve its own capabilities, leading to the new generation deployed in the Gulf War. UAVs emerged as a critical tool for gathering intelligence at the tactical level. These systems were employed for battlefield damage assessment, targeting, and surveillance missions, particularly in high-threat airspace.

Fast forward to today. There’s been an incredible acceleration in the key enabling technologies which has helped UAVs established themselves as serious contenders for many aerial roles. For example GPS has moved from its early days in 1981 where a unit weighed 50kg and cost over $100k to a current cost of less than $5 for a chip-based unit weighing less than a gram. The Internal Measurement Unit (IMU) which measures a drone’s velocity, orientation and accelerations has followed a similar trajectory; in the 1960s an IMU weighed several kilograms and cost several million dollars but today the chipset which puts these features on your phone costs around $1. Kodak’s 1976 digital camera could only manage a 0.1 megapixel image from a unit weighing 2kg and costing over $10,000. Today’s digital cameras are approximately a billion times better (1000x resolution, 1000x smaller and 100x cheaper). And (perhaps most important) the communications capabilities now offered by Wi-Fi and Bluetooth enable accurate and long-range communication and control.

With an improvement trajectory like this you might be forgiven for assuming that UAVs would have largely replaced manned flying in most applications. It’s a cheap technology, versatile and (in military terms) expendable — losing a drone doesn’t carry with it the tragic costs of losing a trained pilot. Yet the reality is that the Mach Loop continues to reverberate with the sound of fast jets and their pilots practicing high-speed low-level maneuvers.

Not invented here?

Continuing to rely on manned aircraft is also a costly option — when a British F-35 Lightning crashed after take-off from an aircraft carrier in 2021 it represented over £100m sinking beneath the waves. So why is the adoption of UAV technology still problematic within major established air forces? It almost looks like another case of ‘not invented here’ — that strange innovation phenomenon in which otherwise smart organizations reject or bury promising new ideas.

At first sight it fits into a pattern which has been around a long time. Take the case of continuous aim gunfire at sea. Sounds rather dry and technical but what it boils down to is that 19th century naval warfare was not a very accurate game. Trying to shoot at something a long way away whilst perched on a ship which is rocking and rolling unexpectedly isn’t easy; most ships firing at other ships missed their targets. A study commissioned by the US Bureau of Ordnance in the late 1890s found an accuracy rate of less than 3%; in one test in 1899 five ships of the British North Atlantic Squadron fired for five minutes each at an old hulk at a range of 1600 yards; after 25 minutes only 2 hits had been registered on the target.

Clearly there was scope for innovation and it took place in 1898 on the decks of a British navy frigate called HMS Scylla, under the command of Percy Scott. He’d noticed that one of his gun crews was managing a much better performance and began studying and exploring what they were doing with a view to developing it into a system. By the time he was in command, two years later, of a squadron in the South China Sea he had refined his methods and equipped his flagship, HMS Terrible with new equipment and trained his gun crews.

Image: Painting by Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg, public domain

The improvements were significant and importantly influenced a young US lieutenant on secondment to the squadron. William Sims learned about the new system and applied it on his own ship with remarkable results; convinced of the power of this innovation he decided it was his mission to carry the news to Washington and change naval practice. What followed is a fascinating story for what it reveals about NIH and the many ways in which it can be deployed.

In his fascinating account Elting Morison highlights three strategies used by the US military to defend against the new idea. The first was simply to bury the idea; Sims’ reports to the Bureau of Ordnance and the Bureau of Navigation were simply filed away and forgotten. The second was to try and rebut the information; the response from the Bureau of Ordnance was along the lines of claiming that US equipment was as good as the British so any differences in firing performance must be due to the men involved. More important was their argument that continuous-aim firing was impossible; when that failed they conducted experiments to try to show there was no significant benefit from the approach. By running them on dry land they were able to cast doubt on the relative advantage of the new approach.

And their third strategy was to try and sideline Sims, painting him as an eccentric troublemaker, stressing his youth and lack of experience, highlighting the fact that he’d spent too long with the British navy and in other ways undermining his credibility. Needless to say this only strengthened Sims’ resolve and he duly went over the heads of the senior staff and appealed to President Roosevelt himself. He finally ‘won’; he remained as unpopular as ever but the new approach was grudgingly adopted and quickly became the dominant design for future naval gunnery.

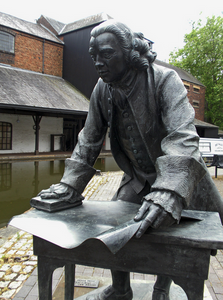

Image: UK HMSO Public Domain

On dry land and a decade later a similar outsider — Major J. C. Fuller — was working with the British Army. He’d seen the possibilities in using tanks as a fast mobile strike capability and his ideas were eventually borne out, briefly in the latter part of the First World War when they were used to good effect in Cambrai and Amiens. But despite being given responsibility for introducing the new technology he met with resistance (not helped by his abrasive nature); there were many who saw tanks as an unwelcome diversion. It didn’t help that the organizational location in the command structure was in the Cavalry Corps — the very group most threatened by the change to tanks. Their post-war strategy was to continue to rely on the equine model; ‘more hay, more horses’ rather than investment in tanks or learning about tank warfare. Elsewhere though his ideas found fertile soil and he was credited by Adolf Hitler himself as the architect of the idea of ‘blitzkrieg’ — the fast mobile warfare which helped overrun France and much of Europe within a few weeks at the start of World War 2.

Drones as disruptive innovation?

Of course it’s complicated but could the case of drone adoption be history repeating itself? One explanation for why NIH happens in this fashion can be found in what we’ve learned about disruptive innovation. When it was published twenty five years ago Clayton Christensen’s classic book exploring the phenomenon ‘The innovator’s dilemma’ had the intriguing subtitle ‘When new technologies cause great firms to fail’. His core argument was that the organizations which were affected by disruptive innovations were not stupid but rather selectively blind, a consequence of their very market success and the organizational arrangements which had grown up over a long period of time to support that success.

For him the challenge wasn’t the old one of balancing radical and incremental change with the losing firms being too cautious. Rather it was about trajectories; whether a new technology was sustaining — reinforcing the existing trajectory — or disrupting, offering a new trajectory. As we’ve come to realize the core issue is about business models; disruption occurs when someone frames the new trajectory as something which can create value under different conditions.

The search for such a new business model doesn’t take place in the mainstream as a direct challenge; instead it emerges in different markets which are unserved or underserved but where the new features offer potential value (often good enough performance at much lower cost). These fringe markets provide the laboratory in which learning and refinement of the new technology and development of the business model can take place.

The problem arises when the new business model built on a new trajectory begins to appeal to the old mainstream market. At this point it’s a challenge to existing incumbents to let go of their old business model and reconfigure a new one. Jumping the tracks to a new trajectory is risky anyway but when you carry the baggage of years, perhaps decades or even centuries of the old model it becomes very hard. That’s when NIH rears its head and it can snap and bite at the new idea with surprising defensive vigor.

There’s almost a cycle to it like that developed by Elizabeth Kubler-Ross to explain the grieving process. First there’s denial — ignore it and it will go away, it’s not relevant to us, it won’t work in our industry, it’s not our core business, etc. Then there’s a period of rationalization, accepting the new idea but dismissing it as not relevant to the core business, followed by experimentation designed not so much to learn as to demonstrate why and how the new model offers little advantage. Variations on this theme include locating the experiments in the very part of the organization which has the most to lose (think about giving tank development to the Cavalry Corps).

Only when the evidence becomes impossible to ignore (often as a clear shift in the market towards the new trajectory and a significant competitive threat) comes the moment of acceptance. But even then commitment is often slow and lukewarm and the opportunity to get on the bus may have been missed.

Meanwhile in another part of the galaxy…

It’s not easy for the innovators trying to introduce the change. They struggle to break into the mainstream because they have no presence in that market and they are up against established interests and networks. Their best strategy is to continue to work with their fringe markets who do see the value in their model and to hope that eventually a cross-over to the mainstream takes place. Which is what has happened in the world of drone technology.

Demanding users in fringe application markets have provided the laboratory for fast learning. Early markets were in aerial photography where the cost of hiring planes and pilots could be cut significantly but where challenges around stability and development of lightweight equipment forced rapid innovation. Or mapping and surveying where difficult and sometimes inaccessible territory could be explored remotely. Once drones were able to carry specialized lightweight tools they could be used for remote repair and maintenance on oil platforms and other difficult or dangerous locations. Their capabilities in transportation opened up new possibilities in logistics, especially in challenging areas like delivering humanitarian aid. Significantly the demands of these fringe markets drove innovation around stability, payload, propulsion and other technologies, reinforcing and widening the appeal.

Estimates suggest the 2021 drone services market is worth $9 billion with predictions of growth rates as high as 45% per year. Application sectors outside mainstream aviation include infrastructure, agriculture, transport, security, media and entertainment, insurance, telecommunication and mining.

Holding the horses?

These days UAVs can do a lot for low price. Just like low-cost flying, mini mill steelmaking, and earthmoving equipment they represent a technology which has already changed the game in many sectors. They qualify as a disruptive innovation but they also trigger some interesting NIH behavior amongst the established incumbents. ‘We’ve always done it this way’ is particularly powerful when ‘this way’ has been around a long time and is associated with a history of past success.

Elting Morison has another story which underlines this challenge. Once again it concerns gunnery, this time the firing performance of mobile artillery crews in the British army during World War 2. A time and motion study was carried out using photographs of the procedure; the researcher was increasingly puzzled by the fact that at a certain point just before the gun was fired two men would peel away and stand several meters distant. It wasn’t until he discussed his findings with a retired colonel from the First World War that the mystery was solved. He was able to explain that the move was perfectly clear — the men were holding the horses. Despite the fact that the 1942 artillery was transported by truck the procedures for horse-drawn guns still remained in place.

Something worth reflecting on when you are walking in those Welsh hills…

Image: Pixabay

Image credits: as captioned, Wikimedia Commons, Pixabay

If you’re interested in more innovation stories please check out my website here

![]() Sign up here to get Human-Centered Change & Innovation Weekly delivered to your inbox every week.

Sign up here to get Human-Centered Change & Innovation Weekly delivered to your inbox every week.

The world of innovation is full of the names of famous partnerships — Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak, Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard, Sergey Brin and Larry Page to name but a few. But Bottger and von Tschirnhaus isn’t a combination which springs easily to the lips or off the tongue. Yet it was this unlikely partnership which managed the impossible — between them they were able to transmute base material into weisses Gold — white gold.

The world of innovation is full of the names of famous partnerships — Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak, Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard, Sergey Brin and Larry Page to name but a few. But Bottger and von Tschirnhaus isn’t a combination which springs easily to the lips or off the tongue. Yet it was this unlikely partnership which managed the impossible — between them they were able to transmute base material into weisses Gold — white gold. Truth was the merchants didn’t know much about it and neither did the Chinese who supplied them. Marco Polo’s best guess at its origins? ‘The dishes are made of a crumbly earth or clay which is dug as though from a mine and stacked in huge mounds and then left for thirty or forty years exposed to wind, rain, and sun …by this time the earth is so refined that dishes made of it are of an azure tint with a very brilliant sheen.” The assumption that this was somehow magical can be seen in an account from 1550 suggested that “porcelain is …… made of a certain juice which coalesces underground…”

Truth was the merchants didn’t know much about it and neither did the Chinese who supplied them. Marco Polo’s best guess at its origins? ‘The dishes are made of a crumbly earth or clay which is dug as though from a mine and stacked in huge mounds and then left for thirty or forty years exposed to wind, rain, and sun …by this time the earth is so refined that dishes made of it are of an azure tint with a very brilliant sheen.” The assumption that this was somehow magical can be seen in an account from 1550 suggested that “porcelain is …… made of a certain juice which coalesces underground…” Which is where another important piece of the puzzle comes in; rather than develop production on a large scale to make porcelain a commodity product Bottger (with Augustus’s backing and the profits from early sales) began to add design into the mix. He commissioned artists to create a range of exquisite artefacts exploiting the potential of the new material and opening up a wealthy market niche to continue to fund his development work. Meissen porcelain figures were used to decorate the drawing rooms of great houses, sculptures took pride of place in entrance halls and even the more mundane business of eating and drinking became a pleasure when using beautifully crafted plates, cups, pots and jugs. What Bottger did was essentially create

Which is where another important piece of the puzzle comes in; rather than develop production on a large scale to make porcelain a commodity product Bottger (with Augustus’s backing and the profits from early sales) began to add design into the mix. He commissioned artists to create a range of exquisite artefacts exploiting the potential of the new material and opening up a wealthy market niche to continue to fund his development work. Meissen porcelain figures were used to decorate the drawing rooms of great houses, sculptures took pride of place in entrance halls and even the more mundane business of eating and drinking became a pleasure when using beautifully crafted plates, cups, pots and jugs. What Bottger did was essentially create

In today’s terms we’d talk perhaps of a rather weak ‘appropriability regime’ — it was hard to keep the lid on what was going on. Samuel Stöltzel was a senior arcanist at Meissen, one of the few who understood the secrets (the ‘arcana’) of making the hard porcelain for which the company had become famous. But (for a suitably high price) he was persuaded to sell these to a competing venture which, in 1717, started to produce porcelain in Vienna. By 1760 there were over thirty porcelain factories in Europe.

In today’s terms we’d talk perhaps of a rather weak ‘appropriability regime’ — it was hard to keep the lid on what was going on. Samuel Stöltzel was a senior arcanist at Meissen, one of the few who understood the secrets (the ‘arcana’) of making the hard porcelain for which the company had become famous. But (for a suitably high price) he was persuaded to sell these to a competing venture which, in 1717, started to produce porcelain in Vienna. By 1760 there were over thirty porcelain factories in Europe. Faced with the challenge of increasing imitation Augustus’s team set about differentiating themselves in other ways. They built a brand, building on the relationships they had already made and the values they and their product stood for — purity, exquisite design, high quality at a premium price. To make sure they got the message across they employed a trade mark — the crossed swords of the Meissen brand which can still be found on their ware today, three hundred years on.

Faced with the challenge of increasing imitation Augustus’s team set about differentiating themselves in other ways. They built a brand, building on the relationships they had already made and the values they and their product stood for — purity, exquisite design, high quality at a premium price. To make sure they got the message across they employed a trade mark — the crossed swords of the Meissen brand which can still be found on their ware today, three hundred years on. Building a business out of an idea and moving to scale needs a system — inside there are many pieces of the jigsaw puzzle to be put in place. As well as commissioning designers to imagine the products the Meissen team also had to continue their hard work on process technology to be able to manufacture them. All the different stages like moulding, shaping, painting, glazing, firing needed to move from manual operations to controlled and systematic processes. Beyond that there were challenges in scaling around procuring raw materials of the right quality, and downstream development of sales and distribution networks.

Building a business out of an idea and moving to scale needs a system — inside there are many pieces of the jigsaw puzzle to be put in place. As well as commissioning designers to imagine the products the Meissen team also had to continue their hard work on process technology to be able to manufacture them. All the different stages like moulding, shaping, painting, glazing, firing needed to move from manual operations to controlled and systematic processes. Beyond that there were challenges in scaling around procuring raw materials of the right quality, and downstream development of sales and distribution networks.