Why planning your innovation expedition helps avoid a lot of trouble on the journey…

GUEST POST from John Bessant

When I was a child a big feature of the social landscape was the annual visit to my uncle’s house on Christmas Eve. My dad came from a big family and they’d gather at his brother’s place to celebrate; my kid brother would already be asleep but I would sit in the small room next to the place they were all gathered, drinking, talking, occasionally singing. It was warm there; a small electric fire in the grate and a blanket to wrap myself in if I felt the cold.

Which was just as well since I invariably spent the evening with my nose in a book. Not just any book; as soon as we arrived I’d make a beeline for the bookshelf and haul out John Hunt’s account of the ascent of Everest. And I’d spend the evening while the ice crawled up the windows outside the room I’d imagine hearing the wind howling against the flimsy side of my tent as we shivered over a primus stove, trying to warm ourselves and get some rest before tomorrow’s big day. The last painful yards towards the summit…..

I was fascinated by the scale of the thing; a huge expedition, involving over 400 people (362 of them porters helping carry the 5000-plus kilograms of equipment) and relying on the intimate knowledge of the mother mountain held by the 20 Sherpas in the team. Those Nepalese guides had grown up in the shadow of the peak and knew to fear and respect it. The months of planning in smoky rooms in London clubs, the assembly and trek towards the base camp and the allocation of roles to help lay the foundations for what would certainly not be a simple walk in the park.

The extended discussions around which paths to take, the weighing up of different challenges along the prospective routes. Obstacles reckoned into the equation and balanced with the specialist skills and equipment needed to tackle them. A whole new language of cols and crevasses, of pitons and crampons to be learned, a crash-course in high altitude physiology and technology to be mastered.

And that was all before they even took their first tentative steps up the slopes.

It was engrossing, exciting and scary; for an 8-year-old kid whose experience of mountaineering extended to scrambling over the South Downs during our annual trip to see Grandma this was heady stuff. And as the evening wore on and we approached the summit, so it became a race against time. For the climbers, whittled down to Hilary and Tenzing, struggling up the last stage, their oxygen and energy running low and storms looming.

And for me hearing the chatter from next door rise to the climax which portended the taking of farewells, the wrapping of my kid brother in a blanket to continue his pre-Santa sleep in the car and me being bundled into a coat. Would I get to the summit in time — or have to wait until next year to continue the journey, abandoning mine at the eleventh hour?

I took a couple of lessons from that book, the first being that I’m not cut out for mountain climbing. There have to be easier and still thrilling ways to get your kicks and ‘because it is there’ isn’t a good enough reason for me to devote my energies to that particular kind of madness.

But the other is a healthy respect for people who scale mountains successfully. It takes a lot of planning, great team work and an approach to uncertainty which is all about agility and pivoting, adapting and improvising your way upwards.

Pretty much the key ingredients for successful innovation — and certainly relevant to another kind of scaling journey, enabling great innovations to have impact.

Because taking an innovation from a small-sized success story to something which delivers value at scale is not an easy one. The Holy Grail of impact has a lot in common with that elusive quest pursued by King Arthur’s knights, taking them along strange paths, meeting with dragons and disasters and lasting a long time. Similar odds of success too.

Having spent a long time focused on the challenges facing start-ups the innovation spotlight is now moving to the question of scaling — and there’s a helpfully growing body of knowledge and codified experience around this theme. Including the important decision about which route to take for the journey to scale.

One thing about mountain climbing which I remember thinking about when reading my Everest book was how they chose which route to take. Faced with 29,000 feet of sheer white walls with the occasional dangerous looking black rock poking its jagged edge through the snow like a knife through a curtain, how do you decide which path to take? It’s not as if there are well-worn tracks and clear signposts which you can follow — all you have is a lot of very unfriendly and treacherous ground on which to try to make your way.

It’s the same with scaling your innovation. Choosing your preferred pathway to scale is a key first stage on the journey; fortunately — like today’s Everest climbers — there’s a wealth of experience available from previous attempts and some important lessons on which we can build.

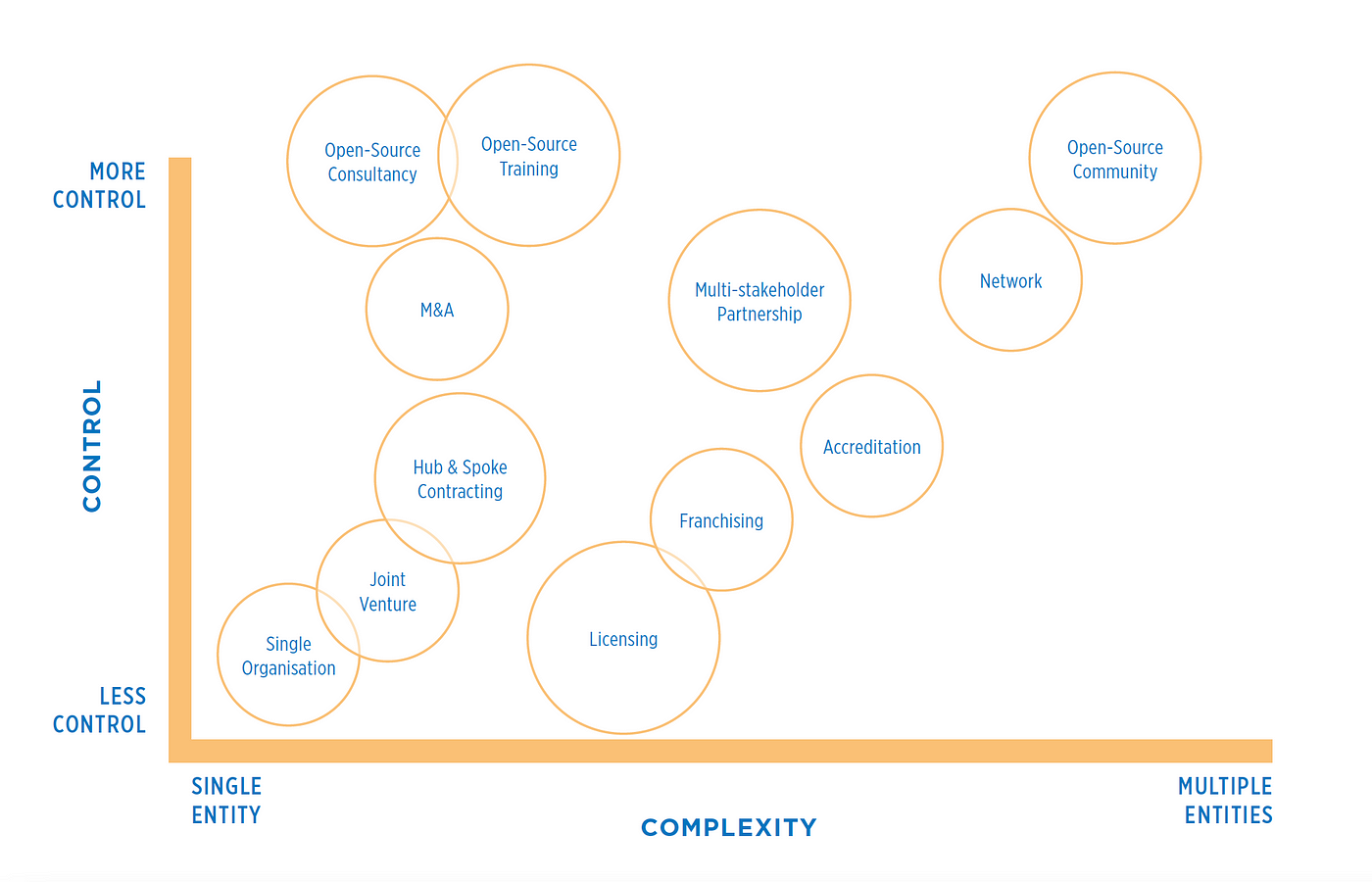

In particular we need to see the choices available as lying on a spectrum where we trade off additional external involvement with giving up a degree of control.

It’s a strategic decision, trying to balance the resource commitments you’ll need to make with the amount of control you want to retain. And with deciding what parts of your innovation knowledge are core, what parts are modular and can be adapted and customized with others in mind and what parts are you prepared to let others engage with, ‘hacking’ their own version of your ideas. Scale stories give us valuable clues about possible options, which include not doing it!

Some innovations aren’t really about a scaling journey. They work for a particular problem in a particular context; what’s needed for impact over the long-term is sustainability, being able to continue to deliver over an extended period of time and becoming something which is used and relied upon.

But if you are going to aim for scale then your choices include:

· Parachute — develop the venture, then try to get acquired, a classic start-up exit strategy. Let someone with the experience and the resources buy your solution, let it go. Easy on paper but you give up all your control and can only watch from the side-lines as your venture develops, and hope it’s in safe hands…

· Go it alone — keep on adding staff and spreading your solution across different geographies, gradually paint the world (or your chosen part of it) in your colors. There are plenty of advantages to doing this — mostly you keep control and you can directly manage quality, message, brand, etc. But the downside is you’ll need a lot of people and resources and you’ll pretty soon reach the point where you need to rethink your structure. The old tight-knit start-up team has to give way to a structured organization, complete with policies, procedures and a slowing down of the decision-making process. Plus you’ll need to adapt your solution to different local conditions — compatibility. And cost management will be important, finding ways to grow without bloating.

In reality this organic growth kind of approach can’t be a solo act — there will be things you need to outsource like legal services, manufacturing, distribution or maintenance. And it can also take time to build your own networks.

· Replicate — maybe your solution idea is one you think will work simply by replicating, placing the same offer in different geographies with only minor tweaks to help it fit. If your solution is something which can be ‘packaged’ and exported — a plug’n’play option — then this can work. It can either be a ‘grow your own’ approach, repeating the pattern by putting down your footprints on an increasingly broad geography. That’s the kind of route followed by IKEA and many other retailers, embodying their innovation solution in something which can be replicated.

Or you can franchise, allow others to take on the task and replicate on your behalf, sharing the revenues and building on your original innovative efforts. That’s the route which McDonalds has followed, exporting its original innovative fast-food format to over 39,000 locations around the world. But as Ray Croc, their scale architect realized, there’s a critical need to make sure the rules are clearly codified and then control via the franchise agreement so your proxies don’t damage the brand, compromise quality or change the core product. It’s a kind of remote control based on a clear constitution….

· ‘Relay replication’ — another version which involves another organization adopting and using your solution. Like franchising it requires protocols, training, standardization of core elements and processes but it also allows the adopting unit to continue to adapt and innovate within agreed parameters. A classic model here might be the diffusion of chemical plants like oil refineries; the core technology is transferred and the user learns to operate. It needs more than simple delivery, not plug n play — it involves a shared extended handover process until the user can make ‘product in a bottle’ with its own staff operating the equipment.

The advantages here are that you learn every time as you coach different organizations in the use of your innovation, plus there’s the chance that their downstream learning feeds back to you and allows you to improve your innovation. But it takes time and resources to ensure a successful handover, with key knowledge being shared through training, manuals and protocols and a long-term commitment to support.

· Licensing is another variation on the replication theme where other players can take on and (depending on the terms of the license) do things ranging from simply selling the core package through to adapting and extending it to suit local conditions. The big advantage is that other players are putting their shoulder to the wheel, helping spread the innovation, plus there’s a direct financial return to the original innovator. But once again it does involve letting go of control.

· Open source/open licensing — much commercial innovation is about finding ways to appropriate the benefits. So there’s pressure to keep a tight rein on what’s shared and how. But if you want to spread something, especially a novel approach, you might want to open up more to accelerate diffusion and seek your returns from being a first mover, growing with the market. There’s plenty of examples — Philips wanted to change the way we consumed recorded music in 1993 when they launched the Compact Cassette and so licensed it for free to others like Sony and Matsushita. It makes sense — if you are trying to establish a new ‘dominant design’ and move the world away from the current incumbent then recruiting others via open licensing is a good road to take.

And in the world of social innovation this has particular relevance; innovators who want to change the world for the better face the same challenge and recruiting others to the cause offers one way of doing so.

There are several advantages to such an open approach, not least it recruits many innovators who may help improve on your ideas. Communities of practice and using the crowd have become powerful innovation engines through this approach of free sharing; Linux is a good example.

Lego’s approach to the hackers who started to modify the original ‘Mindstorms’ product is interesting here; they were presented with a different option to the traditional lawsuit which they might have been expecting. They were invited to Denmark to add their innovative ideas to those of the core design team!

But the downside, of course, in such open approaches is the loss of control and the risk that the innovation may be hijacked or developed in directions which do not match those of the original authors or reflect their social values.

· Strategic partnerships make sense where there is a clear need for ‘complementary assets’ of knowledge or other key resources and where win-win arrangements and contracts can be put in place. Christopher Sholes and colleagues had developed a great solution to the typewriter opportunity back in the 1850s but it took their strategic partnership with Remington and their accompanying mass-manufacturing and marketing to scale their innovation.

· Multi-player consortia may be needed when the range of complementary assets needed goes beyond a single partner. Sears and Roebuck pioneered the remote retailing model with their mail order catalogue approach but they needed to bring together many other players into the model to make it work — finance houses, logistics and distribution and a wide range of different suppliers. Boeing and Airbus do the same today, orchestrating extensive networks of players and partners to deliver their aerospace solutions at scale.

Such consortia bring real power to the scaling challenge but also require careful integration around a core mission. Managing such ‘strategic networks’ is well-known for its high transaction costs and co-ordination challenges.

· Value network and ecosystems — today’s innovation language extends this multi-player game, recognizing that there is a need for multiple players to work together to create value at scale. The challenge is that not all of these players have the same goals or aspirations so balancing their needs with the overall ‘mission’ becomes a tricky balancing act. It’s also important to recognize that such ecosystems don’t just have shared value creators in the mix like our strategic partnerships; they may also involve other players who affect the journey to scale by shaping the ways in which the value creation game is played. Examples of such shapers include government regulators, trade unions and standards organizations.

Once again this has particular relevance for scaling social innovation where system change which delivers real impact may depend on finding ways to bring many diverse players, like government agencies or regional authorities onside. As an influential IDB report puts it, such collaborations require ‘…different actors to coalesce around a shared set of priorities and best practices’.

· Platforms — we’re also now seeing the rise of platform businesses which enable scaling through linking innovators and markets more effectively. The Taobao market approach pioneered in China mimics in many ways the ecosystems around Apple’s developer platform or much of the Amazon operation. For small start-up innovators such platforms become a powerful alternative route to scale, but at the cost not only of accessing the platform but also in letting go some degree of control.

For any innovator climbing Mount Scale remains a key challenge. Meandering around the foothills may be a pleasant way to pass the time but if you want your innovation to have real impact then that peak has got to be climbed. Which means putting together and planning your expedition with the kind of care and attention John Hunt brought to his Everest team. And my guess is that his reflections probably have relevance in the world of innovation. Working out the most appropriate route up those slopes is something best done in the comfort of base camp rather than halfway up the mountain with the wind howling and the snow lashing at your face as you realise that the other path might have been a better one to take….

This blog is based on our forthcoming book ‘The Scaling Value Playbook’ — click here for more details and to pre-order

You can find my podcast here and my videos here

And if you’d like to learn with me take a look at my online course here

Image credits: Dall-E via Bing, John Bessant

![]() Sign up here to join 17,000+ leaders getting Human-Centered Change & Innovation Weekly delivered to their inbox every week.

Sign up here to join 17,000+ leaders getting Human-Centered Change & Innovation Weekly delivered to their inbox every week.